Tax residency for fun and profit

Tax rules, which describe what portion of one’s profit needs to pay to the government, are famously complex. If they involve multiple countries, they are even more confusing. Having moved to a different country for the 2020 pandemic, I studied the regulations in detail and decided to write down my observations for the future.

Rule of law 101

One can summarize the general process of setting up tax law in a simple way (even though the rules themselves may be complex):

- Parliament votes on legislative acts which decide on details of who, when, and how much tax should pay.

- The act is published (“promulgated”) in an official bulletin and becomes law.

- Courts resolve the disagreement between the taxpayer and tax authorities, and civil officers (bailiffs, police, etc.) enforce compliance.

Sovereignity of the country guarantees that the law enacted in this way usually applies only on its territory. For example, it’s not possible for folks in Bundestag to decide on what taxes should residents of Sydney pay.

Double taxation agreements

Limiting the taxes to the territory of a state doesn’t solve all the international taxation issues.

For one, it shouldn’t be possible to evade taxes just by making repeated trips to a tax haven (area of low rates of taxation) on the day one’s salary is paid. On the other hand, a country doesn’t want to impose regular income taxes on tourists or attendees of a business meeting even if they happen to be physically present under its jurisdiction on their pay date.

As taxation systems (and the political power) differ significantly between countries, it feels impossible to set a single, precise set of tax rules that all countries could agree to. For this to happen, one would need to consider all possible taxes and exact situations when they should or shouldn’t be levied.

Instead of that, countries opt for bilateral treaties where pairs of countries (e.g. Germany and France) agree on which country has the right to tax different types of income. Such a treaty is called a Double Taxation Agreement (DTA).

OECD model tax convention

Even though getting all countries to agree on a common set of rules in a binding treaty feels like a lost cause, there are some general rules that countries want from their DTAs.

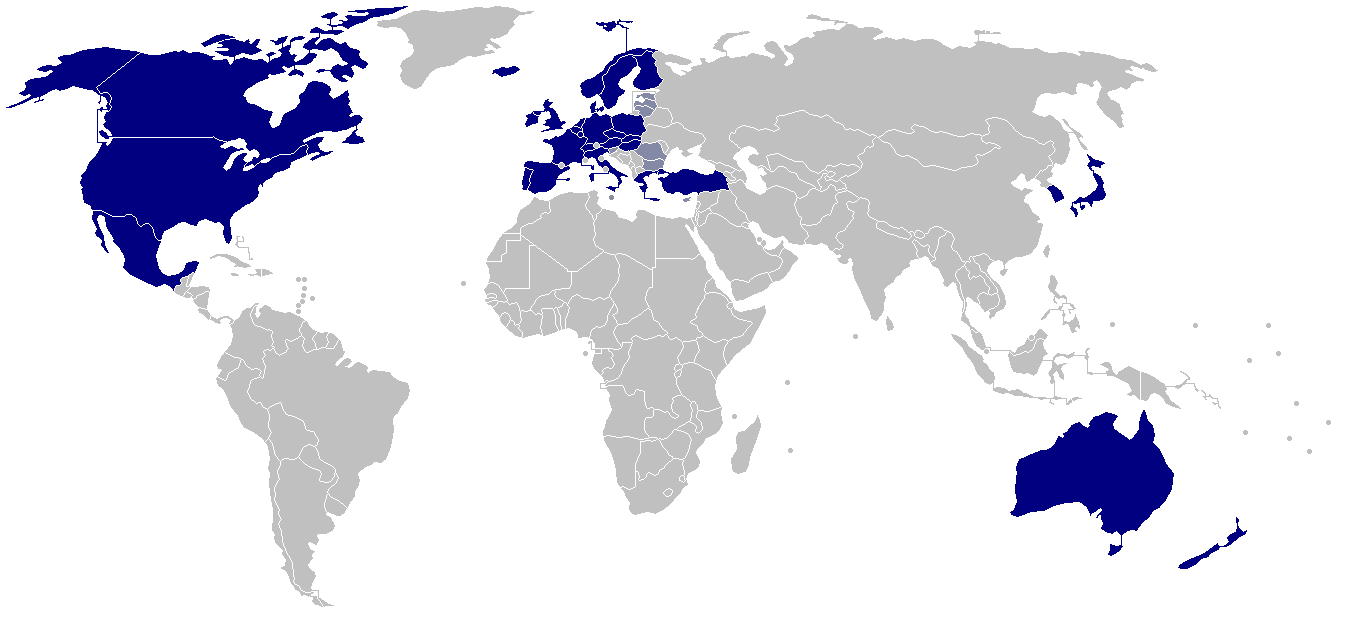

To simplify the process of writing the tax agreements with others, several Western countries, grouped in an intergovernmental organization OECD1, prepared a model tax convention which forms a common ground, helping them to start drafting the treaties.

The tax convention tries to formalize the idea of a person being liable for tax only in one country: the one where they live. While the details on the rates, procedures, or exemption methods differ between DTAs, the principles are the same in the DTAs of OECD countries. Let’s review them below.

Tax residency

The crucial concept defined in the model tax convention is tax residency. It’s meant to be a unique country where a given person generally pays taxes for their worldwide income.

The content of the article of the model convention defining tax residency:

Article 4: Residence

For the purposes of this Convention, the term “resident of a Contracting State” means any person who, under the laws of that State, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature, and also includes that State and any political subdivision or local authority thereof. This term, however, does not include any person who is liable to tax in that State in respect only of income from sources in that State or capital situated therein.

Where by reason of the provisions of paragraph 1 an individual is a resident of both Contracting States, then his status shall be determined as follows:

- he shall be deemed to be a resident only of the State in which he has a permanent home available to him; if he has a permanent home available to him in both States, he shall be deemed to be a resident only of the State with which his personal and economic relations are closer (centre of vital interests);

- if the State in which he has his centre of vital interests cannot be determined, or if he has not a permanent home available to him in either State, he shall be deemed to be a resident only of the State in which he has an habitual abode;

- if he has an habitual abode in both States or in neither of them, he shall be deemed to be a resident only of the State of which he is a national;

- if he is a national of both States or of neither of them, the competent authorities of the Contracting States shall settle the question by mutual agreement.

Where by reason of the provisions of paragraph 1 a person other than an individual is a resident of both Contracting States, then it shall be deemed to be a resident only of the State in which its place of effective management is situated.

In simple words, if both signatories of the treaty want a given person to pay tax on its worldwide income, there is a set of criteria to review to determine in which (single) country the person will be considered a tax resident (likely giving it the right to tax their worldwide income).

Country-specific tax residency criteria

Thanks to the criteria overriding national laws on tax residency, countries can set the rules freely in their local legislation. Even if the country-specific rules would overlap, making a single person “tax resident” in multiple countries based on their national law, the DTA will describe how to choose a single country for tax residency.

A commonly used criterium for tax residency says that a person who resides in a given country for more than 183 days in a given tax year is tax resident there. If every country used only this provision, there wouldn’t be any issues with multiple countries claiming overlapping tax residency. It’s often the case though that, apart from 183 days, there is an additional criterium saying that a person who has a house, family, or a “center of vital interests” in a country, would be considered tax resident there, even if they spent most of the year abroad.

There are also some countries where even a short stay triggers tax residency; for example, in Switzerland, a working individual becomes tax resident after 30 days of stay. The overlapping tax residency may thus happen, and the use of DTA criteria may be necessary to establish a single country of tax residency.

No tax residency

As countries decide on their tax residency rules without much regard to other countries’ regulations2, it may as well happen that a given person is not considered a tax resident in any particular country based on its laws.

For example, a person moving between 3 countries without his “center of vital interests” and spending less than 183 days in any of them due to frequent business visits may have no tax residency.

Does it mean such a person doesn’t have to pay any taxes? Of course not :) The countries often have rules saying that non-residents pay taxes on the portion of the income arising from that country. If a person is tax resident elsewhere, they may use the DTA to override the “non-resident paying local taxes” rule. If they are not resident in any country and are non-resident in multiple countries, they would be paying local taxes in each of them. They won’t be able to use DTAs in that case, as the DTA only clarifies the criteria for overlapping tax residency, i.e. multiple countries wanting to tax a person on the worldwide income.

Changes within the (tax) year

The country-specific rules for tax residency are often expressed in terms of the whole tax year, e.g. “a person is tax resident for the whole tax year if they spend at least 183 days during that year”.

What happens when someone’s situation changes in the middle of a year, by buying a home or permanently moving to another country in June?

The DTA solution is simple: it is not concerned about tax years at all (which may run differently in the two countries, e.g. in the UK the tax year starts April 6th). Instead, all of its provisions apply at any given moment; if someone’s circumstances change on June 15th, they may be considered a tax resident of one country until June 14th and the resident of another from June 15th onwards. It would give each country the right to tax only the portion of the income earned in the corresponding part of the year. Then, the countries typically apply their regular tax brackets only to the “home” part of the tax year.

Income from employment

Most articles of the model tax convention explain which country possesses the taxation right for a particular type of income. Let’s take a look at article 15, describing income from employment.

Article 15: Income from employment

- Subject to the provisions of Articles 16, 18 and 19, salaries, wages and other similar remuneration derived by a resident of a Contracting State in respect of an employment shall be taxable only in that State unless the employment is exercised in the other Contracting State. If the employment is so exercised, such remuneration as is derived therefrom may be taxed in that other State.

- Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraph 1, remuneration derived by a resident of a Contracting State in respect of an employment exercised in the other Contracting State shall be taxable only in the first-mentioned State if:

- the recipient is present in the other State for a period or periods not exceeding in the aggregate 183 days in any twelve month period commencing or ending in the fiscal year concerned, and

- the remuneration is paid by, or on behalf of, an employer who is not a resident of the other State, and

- the remuneration is not borne by a permanent establishment which the employer has in the other State.

- Notwithstanding the preceding provisions of this Article, remuneration derived in respect of an employment exercised aboard a ship or aircraft operated in international traffic, or aboard a boat engaged in inland waterways transport, may be taxed in the Contracting State in which the place of effective management of the enterprise is situated.

The article presents a general rule, saying that salary should be taxed in the country of tax residency unless the work is happening in the other country when the salary can be taxed by both countries.

It also adds an exception that even if the work happens in a country where the worker is non-resident (according to the treaty), if the worker is present there at most 183 days in any period of 12 months (and some other conditions are satisfied), only the residence country has the taxation rights to the salary.

This exception is important for people spending short amounts of time in other countries, for example attending conferences or business meetings: without it, every short-term visit to a different country would give taxation rights to the income earned while in the other country.

Methods of eliminating double taxation

What happens when this exception cannot be applied, and the salary can be taxed by both countries? It may occur when the employer sends the worker to supervise a project abroad for a year.

As allowing both countries to tax the same income would be harmful to the worker and discourage international collaboration, countries agree in a DTA a method for exempting the income taxed in the other country from taxation to some level.

Typically, the residence country (the one having the right to tax the worldwide income) offers the taxpayer an exemption to bring the total level of taxation somewhere close to the maximum level that the person would suffer in any given country.

It can be realized in a couple of different ways: using tax credits, exemption with progression, or proportional exemption.

Let’s assume the residence country taxes has two tax brackets: 10% for the income until 100 units and 20% afterward, and the non-residence country taxes everything at 15%, and see an example of how the different methods work out in practice.

Tax credits

With tax credits, the residence country decreases the tax due by the amount of tax the worker pays in the other country.

| Kind | Residence | Non-residence |

|---|---|---|

| Income | 100 | 20 |

| Tax | 10 + 4 | 3 |

| Credit | 3 |

The residence country taxes the worldwide income (120), with the first 100 taxed 10% (10), and the next 20 at 20% (4), and decreases the tax by the amount paid in non-residence country (3).

Exemption with progression

When the country allows exemption with progression, instead of decreasing the tax directly, they only tax the income earned in the residence country, but the tax brackets take into account the income earned abroad. Let’s see the same example:

| Kind | Residence | Non-residence |

|---|---|---|

| Income | 100 | 20 |

| Tax | 8 + 4 | 3 |

The residence country taxes the first 80 in the first (10%) bracket (as 20 of the first-bracket allowance was used up by the foreign income). The remaining 20 is taxed in the second bracket (20%, 4).

Proportional exemption

The proportional exemption has some elements of the previous two methods of eliminating double taxation. Here, we first calculate the total tax and exemption as in the tax credit example. Then, we calculate the proportion of the paid tax that corresponds to the income earned abroad. If this proportion is higher than the tax credit, only that proportion is allowed as a credit.

| Kind | Residence | Non-residence |

|---|---|---|

| Income | 100 | 20 |

| Tax | 10 + 4 | 3 |

| Credit | 2.33 |

Proportion of the tax for the income abroad: 20/120 * 14 = 2.33. In this case, the tax due in the residence country will be 10 + 4 - 2.33.

One needs to remember that these three kinds of exemptions are just examples, and the countries are free to agree on any exemption method they find appropriate in their DTAs.

Commentary

The model tax convention (and any particular DTA) is relatively short: it has 20-something articles, around 1 A4 page each. It cannot possibly describe any possible situation in detail. As a complement to this document, OECD published a much lengthier, 380-page long, Commentaries on the articles of the model tax convention. It describes the tax convention articles and the reasoning behind them in more detail, giving practical examples. While it’s non-binding (as only the particular DTA is binding), various courts use it to help them interpret the articles of the DTAs.

Enforcing the agreement

We know what to do when we think a country-specific law is violated: we go to the court, and it makes a judgment. But what to do if the two countries’ institutions have different interpretations of the DTA, e.g. when both countries claim “you are considered a tax resident of our country”?

Mutual agreement procedure

As we said earlier, referring an issue to a court in any particular country may not work, as their jurisdiction won’t cover the other state (after all, the other country’s courts may disagree!).

To give the taxpayer a mechanism to get a binding interpretation of the DTA, the countries agree to a special legal process, called Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP).

It is initiated by the taxpayer who claims that the resolutions of the DTA are not followed by one of the countries. Both countries take part in the process and are trying to agree to a common interpretation. If they fail to do so within a time limit, the issue is referred to somewhat independent arbitration.

Given that MAP requires engaging both countries’ legal teams, it looks like a slow process one would prefer to avoid.

Final words

The international tax rules are complex, and the countries’ tax authorities often want you to pay all of the tax to their country. It’s worth knowing under what conditions you have to do so and when to claim taxation is not appropriate.

Understanding the rules may help you to pay less tax, as sometimes changing your decision (e.g. buying a house, selling stock, moving countries at a different time) may lead to your income being taxed in another country that has a lower tax rate.

Disclaimer

As I am not a tax professional, you should take the information above as a grain of salt.